#50 1914-1945 The Unforeseen Consequences: The Loss of Global Financial Control

One of the great benefits of this blog is that we can view elements world from a historical perspective. The period between 1914 and 1945 saw a world in flames when everything that had been created over the previous 100 years was in crisis. The global economy was one of these elements.

The capitalism of the 19th century had developed a global system of trade and investment for the first time in world history; all based within a system of colonial ownership. The economic system itself was and has always been unstable in the sense that some years saw rapid growth and some years growth declined. But though these ups and downs had proven unpleasant, they had not threatened the heart of the new economic system.

Private property for the first time became the dominant method to handle land and industry. Banking had grown in importance. The entire edifice was premised on a stable system of exchange; this was the pound sterling which acted as the world's currency. Gold had become the ultimate standard of value for all the major non colonised countries.

The British government at an early stage, in 1916, limited their adherence to the system and by 1931 removed the system altogether. The essence of the global capitalist system, that is the mechanism that held it all together, ceased to work.

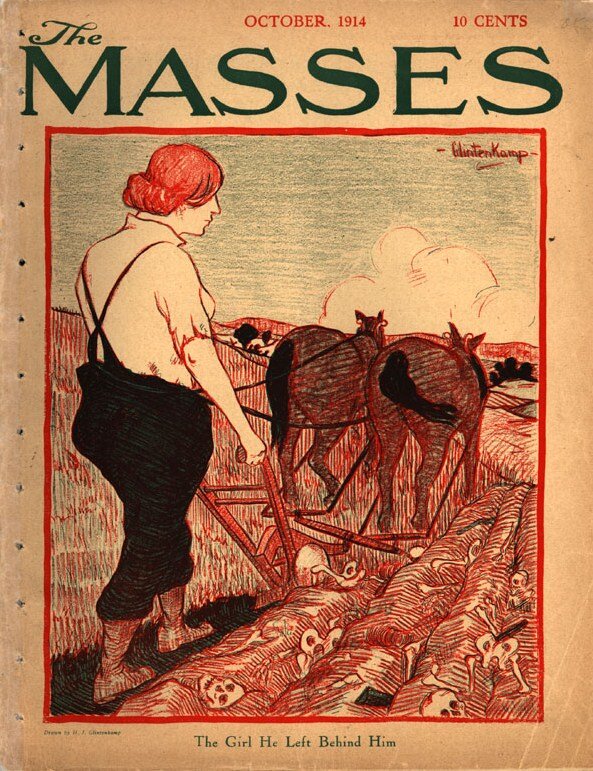

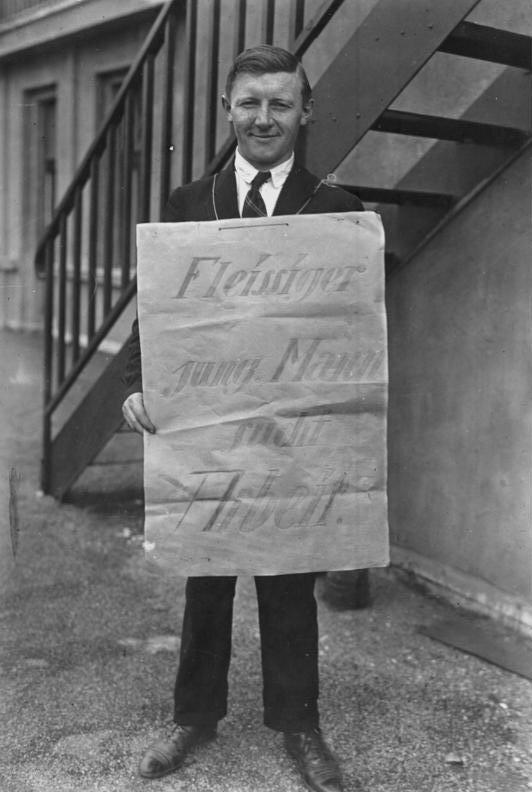

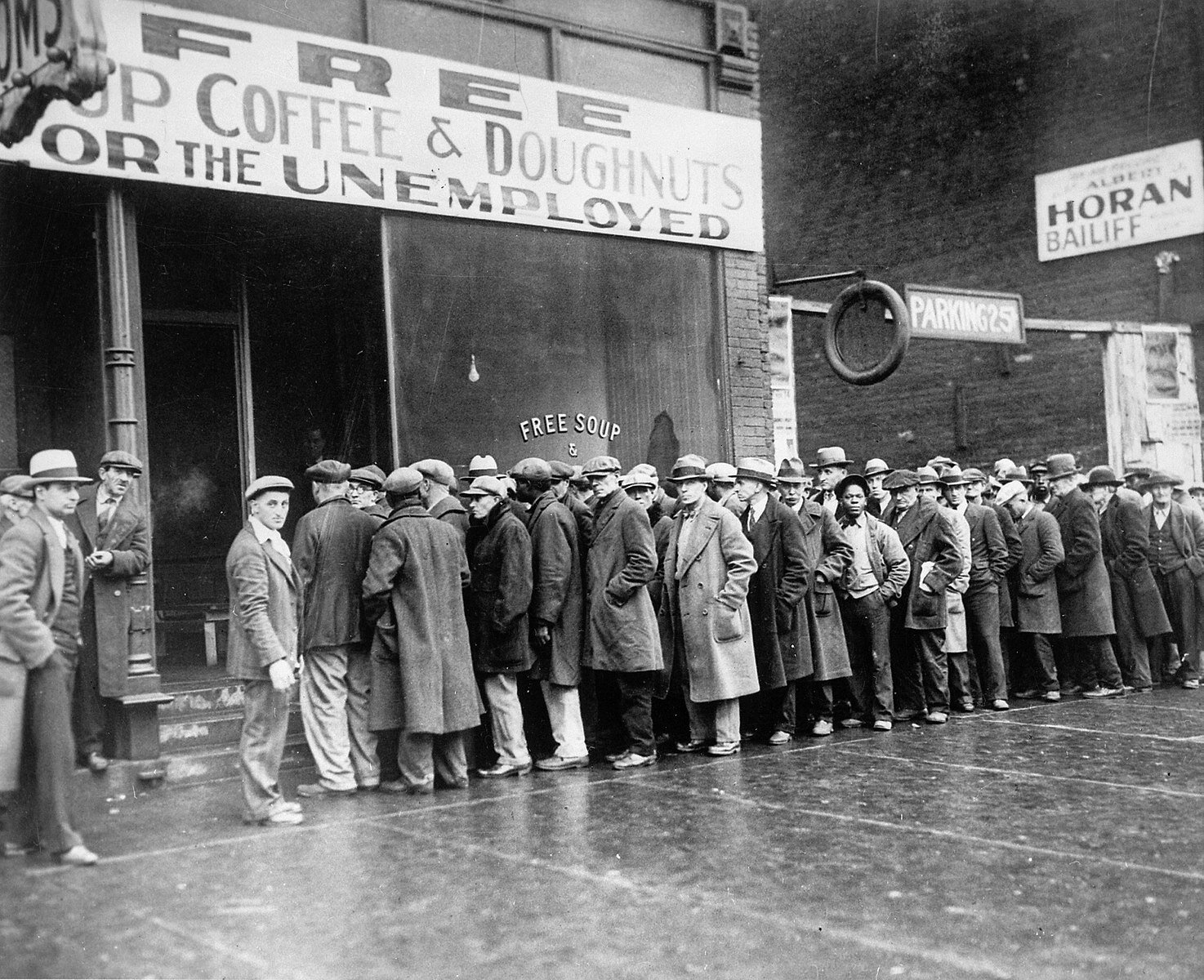

The years 1918 to 1939 were perhaps not unsurprisingly financially chaotic. The main national economies affected by world trade and the movement of capital, that is all the major belligerent powers of the 1914-18 war, moved from massive inflation to deflation, from rapid growth to massive downturns. With these movements of the national and global economies, people suffered from hunger and a constant lack of work. Not surprisingly it was in these conditions that political turbulence and the growth of fascism arose across all the major European nations. Equally unsurprisingly, the German economy suffered the most extremes of the slumps and depression.

These facts are well known. The core of the global economy in the 19th century had been the Gold Standard and the free movement of capital and trade (often described as laisse faire) across national boundaries. All the men of political power alongside the central banks attempted to recreate the structures of the 19th-century world economy. Debate among economists has repeatedly gone back to these 20 years as the epitome of world chaos. J M Keynes’s macroeconomics has continued to play a key role. To this day, a similar argument continues.

The Failure of the Gold Standard

The Gold standard had been the heart of the international system. It provided nations with the ability to trade and invest beyond their borders, a national and international stable currency, and exchange rates between gold and paper money. It had limited the availability of cash and thus stabilised inflation and the volumes of debts:

As J.M Keynes explained:

“The various currencies, which were all maintained on a stable basis in relation to gold and to one another, facilitated the easy flow of capital and trade to an extent the full value of which we only realise now, when we are deprived of its advantages. Over this great area, [referring to the empires of Russia, Austria Hungary and Germany] there was an absolute security of property and person. These factors of order, security, and uniformity, which Europe had never before enjoyed over so wide and populous territory or for so long a period, prepared the way for the organisation of that vast mechanism of transport, coal distribution, and foreign trade which made possible an industrial order...”

- J M Keynes, The Economic consequence of the Peace, page 11

In 1914, all the major belligerent countries had come off the Gold Standard. The war had been paid for by creating new bank loans, printing banknotes, increased taxation and the selling of war bonds.

By 1918, all the countries involved in the war had huge increases in public debt by up 1000% and had increases in inflation by 200 to 300%. The ratio of gold reserves to cash had declined for each major country from around 60% to 10% and for Russia from 98% to 2%. Britain was best off with a decline in ratios from 52% to 32%.

After 1918, the countries that lost the war or were involved in revolution - Russia, Poland Hungary, and Austria - all experienced runaway inflation. While all the public debts were wiped away, money became worthless for a while, chaos reigned, and suffering was widespread.

There had been no global institutions like the United Nations and its multi-institutionalised global offshoots which were created after 1945; nor were there financial institutions such as the likes of the World Trade Organisation, the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank. The Gold Standard was in effect the sole globally accepted international institution that held the world’s financial world together.

Between 1815 and 1914, the British, as the world's leading power, had always claimed that they had followed a 'balance of power' approach to foreign relations in Europe, that is an ‘equilibrium between nations' as the foundation of the international system. Certainly, diplomacy became an art form. And there is no doubt that the British believed what they preached. As we now know, when the most powerful global nation attempts to maintain the status quo to its benefit, small nations suffer.

Financial Chaos

Much of my analysis in this blog, and preceding blogs, has been taken from Carroll Quigley’s Tragedy and Hope. These 20 years have also been studied by many economists and economic historians. They have been understood as the ultimate example of capitalist chaos, as they are often remembered and referred to whenever there is a global downturn.

J.M Keynes’ first important work The Economic Consequences of the Peace (1919) and then The General Theory of Employment, Interest, and Money were written as a testament to the importance of this period of history, and how to avoid in future the horrors of the 1920s and 30s. Keynes’s theory is still debated by economists today. His ideas were put into practice after 1945 and accepted by politicians until 1970 when they were discarded.

The financial chaos of this period was in part the wider reflection of the growing loss of global political power of the leading world power Great Britain. The global economic chaos provided the new aspirant world power – the USA – the opportunity to gather the intellectual forces in preparation for her take over from Britain, which she succeeded with in 1944 at the village of Bretton Woods in North Eastern USA. I will detail more of this in future blogs, however.

Bretton Woods has gone down in history as the start of a new beginning. The Americans had not been sitting idly by. They had been examining the global landscape over these turbulent years. They began to put in place a new institutional base to stabilise the world’s economic system. I shall deal with these new institutions in later blogs. They set up:

The United Nations to control world politics

The World Trade Organisation to control global trade

The World Bank and the International Monetary Fund to control the flows of investment for short and long term

The International Labour Organisation ILO to control international labour

A fixed exchange rate based on gold and the US dollar

These institutions have been debated ever since. Generally, we can say that they provided the base starting point to reinvent a broken system of world capital flows.

Copyright Notice. This blog is published under the Creative Commons licence. If anyone wishes to use any of the writing for scholarly or educational purposes they may do so as long as they correctly attribute the author and the blog. If anyone wishes to use the material for commercial purpose of any kind, permission must be granted from the author.

Ideology alone was of course not enough for Hitler to rise to power. The question remains: how was Hitler able to revive the German economy sufficiently to fight a global war in a mere six years? Hitler had taken political power in Germany in 1933. Once this question has been asked, the direction of the answer is obvious: the German economy would have to be supported by the great powers, France, Britain or America; there was no other way.