#3 The Ancient system of Globalisation: The Silk Road; Trade from East and Central Asia through Russia, and The Mediterranean

The Silk Road: The Ancient System of Globalisation

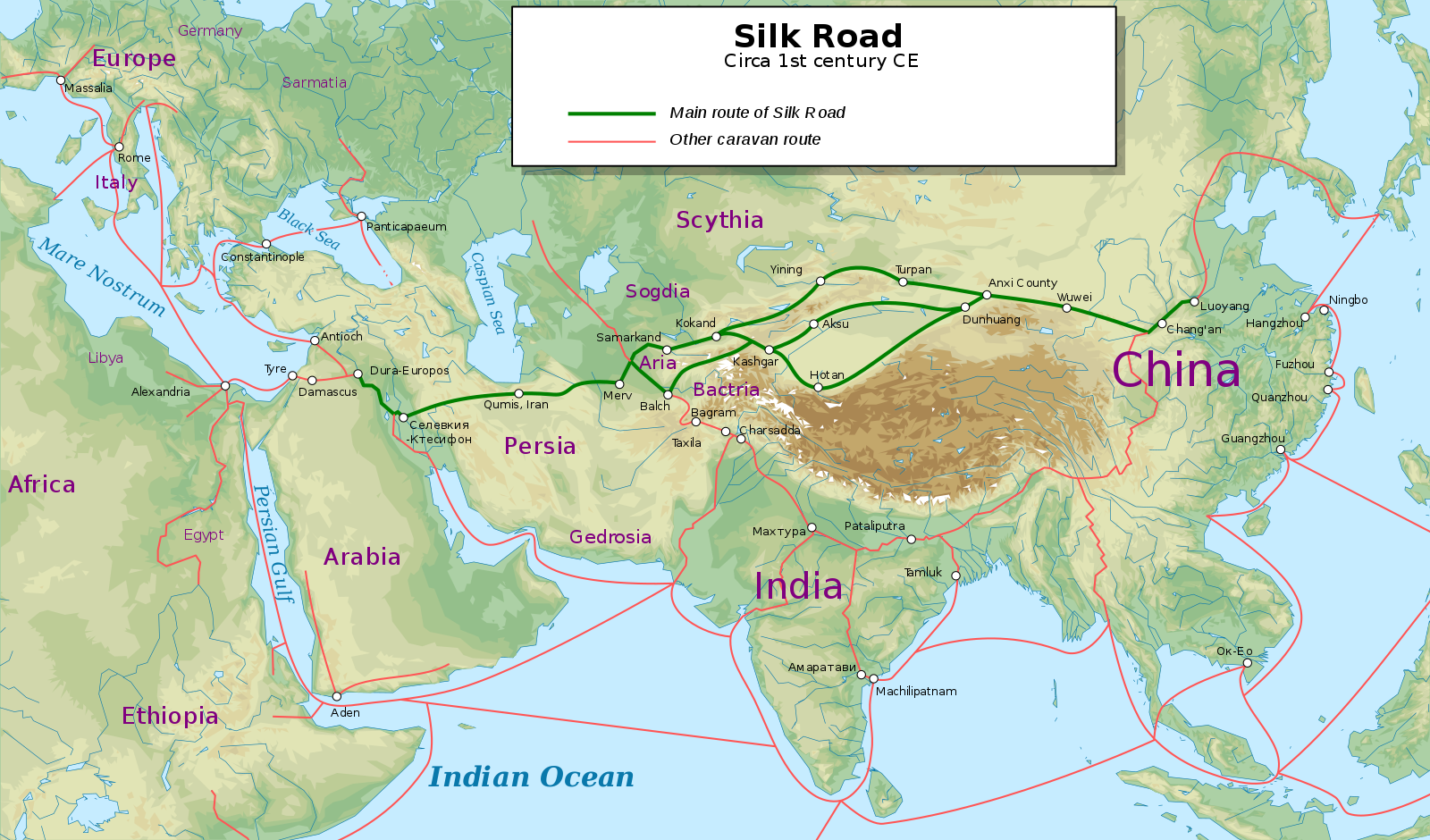

Before 1453, which was when the Ottomans captured Constantinople, the major route of world trade had been from Asia westwards through to the Middle East and Europe. This dynamic of trade had arisen from the east and Europe at the time was a relative backwater compared to the continents of India or China.

"Silk Road in the 1st Century AD" by Kaidor is licensed under CC-BY-SA-4.0

Trade came by a multitude of routes, by land and by sea. The land routes could take the traveller through Kabul, Esfahan, Baghdad and Damascus, or further north, along the rivers and pastures of today’s Russia and then further into the northern European states. We know that these global trades had been in operation since prehistoric times and have evidence from archaeological excavations that traded goods could end up as far as Scandinavia or the Orkney Islands of Scotland.

There were also sea routes from China and India, through the Persian Gulf and Red Sea and into the Mediterranean. From there, goods were shipped to various European centres of population. These voyages, largely with small sailing boats, would take some three months and a complex arrangement of stop-off points were well established to provision them.

As scholars have researched the silk road from India and China, the complexity and sophistication of these trading systems have become apparent. Traders and bankers operated in both East and West, writing letters to each other, offering opportunities to friends and relatives. Trust and family ties were important in this context.

Constantinople, now known as Istanbul, was a major trading hub joining East with West and a key stopping-off point for travellers. Traders arriving in Constantinople could move south, north or east from this significant vantage city. So, in 1453, when the Ottomans took control of the city and its surrounding trade routes, they began to dominate the trade eastwards. It was from this time that Europeans began to search for new ways to the east; principally down the west coast of the African continent, around the Cape and into the Indian Ocean. They also began to sail westwards across the Atlantic, mistakenly thinking that this might be a way to the East.

“Map depicting the Ottoman Empire at its greatest extent, in 1683” by Atilim Gunes Baydin. This map shows how the Ottoman Empire controlled land around the Red Sea, Egypt, parts of the Arabian Peninsula, and northern lands in the Mediterranean. View details

In terms of produce reaching Europe, there were two parts to the silk route. There were the long routes from the ports of India and China, through the Red Sea or the Gulf of Aden, either into Egypt or to the centre of the Arab world. This journey might take a camel caravan three months. Then there was a second, shorter journey into all parts of Europe.

The first part of the silk road route was taken by many traders journeying on horse or camel and dhows from the Gulf region. We know more about this journey due to an astonishing cache of papers discovered thirty years ago in an ancient Jewish synagogue located in Old Cairo in Egypt. Contracts, letters and other documents had been deposited at the back of a mosque and lay there for hundreds of years, preserved by the dry conditions of the desert air. This unique set of documents was written in many languages, detailing the activities of this ancient trade route.

The second part of the silk route trade consisted of all the ports now in Syria, Palestine, through Constantinople, and into the Mediterranean area, then controlled by the Venetians, Genovese, Romans and Neapolitans. These city-states were constantly at war with one another for control of this trade. Venice attempted to control associate territories such as Crete, in its attempts to monopolise the trade through Constantinople. The Ottomans warred against the Italian city-states to control ancient trade routes in the Mediterranean.

Any visitor to Venice today can marvel at the ancient architecture arising from this time. The city had once been a great emporium, forwarding goods such as silk and cotton to other European cities. Venice’s wealth had been built on its people’s seafaring and shipbuilding skills, and not least their ingenuity. Marco Polo, one of the earliest European visitors to China, had been a Venetian nobleman.

The ancient silk routes from China and India through Central Asia and into Russia and Europe was the old system of globalisation. By ‘globalisation’ I mean the processes by which states and regions become interconnected through trade, exchange of culture and migration of peoples. The silk road would wane as the dominant element of world trade in the 1600s when the major European kingdoms formed monopoly companies. These companies, such as the East India Company created independently by the French, Dutch and British, created a new system of global trading organisation. In later blogs, I document most of the monopoly companies created after 1600. By 1800, these companies had become the new globalised system of trade and the Silk Road system slowly fell into abeyance. The new monopoly global companies constituted truly global systems of trade. These companies not only traded with China and India, but with Africa and the entire Americas. This is, of course, a simplification of the processes at work. What’s important to understand is that globalisation is not a new phenomenon, rather it is that over the last 500 years globalisation has changed and changed again.

Ancient and Capitalist Imperial Expansions

Map of the World in the year 1 CE. For the full map click here

Ancient Russians, Ottomans, Chinese, Moghuls and Incas had all conquered other peoples. However, these ancient versions of imperial expansion had rarely been as transformational as the colonial conquests under examination here. The Incas had no writing, wheels or horses, yet they conquered and held territory over long distances and engineered the land to high standards. But generally, the way of life, religion and technology in the areas of conquest were left more or less alone. Local forms of government remained in place, as long as tribute was paid to the centre.

The European conquests, by contrast, created a new and utterly unique world. European colonial powers invaded new faraway territories, fighting amongst themselves, and destroyed many societies in the process. They created original new empires, which lasted until they were blown away in historically unprecedented bloodletting from 1914 onwards. Historians of all stripes have described this process as ‘modernisation’. ‘Modern’ is a colloquialism, used but rarely defined. The transformations which the European capitalist powers brought to their colonies, from the earliest invasions, were the notions of private property, secular thinking, racism and Christianity. Importantly, they did not bring industrialisation.

Over a period of 450 years from 1492, the new European imperialists defeated and destroyed the old Empire, the Inca and the Aztec empires. In the Americas, the Inca Empire was destroyed. In Europe, the Holy Roman and Austro-Hungarian empires were likewise swept away. In the Middle East, the Ottoman and Egyptian empires were weakened and then destroyed in the early 20th century. In the east, the Mughal Empire was defeated in 1767; and finally, the Chinese empire was destroyed by 1914.

The destructions of the old empires varied in terms of time, place and intensity, though none could escape the onslaught from the new all-conquering capitalist empires from Europe and North America. Only Japan in the late 19th century was able to alter its internal political economy to compete on equal terms. We shall come back to this example later in this blog.

Conclusion

The structural changes under consideration in blog 3 are often written about in terms of the Renaissance from the 14th to the 17th centuries, and the Protestant Reformation from 1517 to 1647. Both concepts are often deemed to be positive in retrospect and regarded as great European success stories in the context of ‘modern’ thinking. Often figures and features such as Michelangelo, Leonardo da Vinci, the beginning of science-based observation, and magnificent new churches and mosques in Istanbul in the 16th and 17th centuries are highlighted. But both the Reformation and the Renaissance were key elements in the destruction of the old feudal system and recreation of a new world order, where flows of gold and silver from the Americas and the destructions of ancient civilisations in the Americas were essential parts of a world in rapid change. As I have shown in this blog, although the ancient silk routes from China and India formed an older system of globalisation, this began to wane in the 1600s. What it gave way to was the creation of monopoly companies that, by the 1800s, comprised a truly global system of trade. I discuss in greater detail in later blogs the role of monopoly companies in beginning to transform the world.

Suggested reading

The history of the Silk Road has attracted many fine scholars. The subject covers millennia and there is a continuous supply of new research on this subject. I have provided only a brief introduction here. Janet Abu Lughod Before European Hegemony: The World System AD 1250 to 1350 provides perhaps the best comprehensive introduction with a multitude of excellent maps.

Joseph Needham has to be the first great scholar in the English language, see Robert Temple's Introduction to Needham’s work: The Genius of China: 3000 years of Science, Discovery and Invention, Touchstone Books, 1989.

Janet L Abu Lughod: Before European Hegemony: The World System AD 1250 to 1350. Oxford University Press, 1989.

Andre Gunder Frank: Reorient Global Economy in the Asian Age. University of California Press, 1998.

Sandra Halperin: Re-envisaging Global Development. Routledge, 2013.

Peter Frankopan: The Silk Road: A New History of the World. Bloomsbury, 2015.

Elif Shafak’s The Architects Apprentice (Penguin, 2015) is a novel set in Istanbul in 1574, and is about Sinan, one of the world greatest architects.

Note: Historians have been using modernisation as a concept for a long time, nearly always leaving it to the reader to intuitively understand the term. Modernisation is an oblique way of referring to private property, secularisation, and so on. Normally it is left to the reader to interpret the term.

Copyright. The copyright of this blog is as follows: It is published Under the Creative Commons licence. If anyone wishes to use any of the writing for scholarly or educational purposes they may do so as long as they correctly attribute the author and the blog. If anyone wishes to use the material for commercial purpose of any kind, permission must be granted from the author.

By the time of the French Revolution in 1789, the Americas had been invaded, slavery had been introduced on an industrial scale and the eradication of the native populations was well underway. Africa was being denuded of its young people and the process of impoverishing India had started. The balance of the world’s power and wealth had shifted and reversed. The wealth of China, India and the rest of Asia would be radically diminished, all on a historically unprecedented scale.